|

Take a tip from the original frequent

fliers

Why are observers in temperate climates so fascinated by bird

migration? Because birds make us feel like chumps as they head for a

sensible climate and leave us to deal with the snow and ice. But

birds don't have maps -- so how do they know where they're going?

And how do they get the energy to get there?

...Could you hold off on the

questions for a moment so I can dish out some answers?

Navigation

How do birds find their way? Simple. Through a combination of

-

Sighting (they don't call it a

"bird's eye view" for nothing) features like rivers, coastlines,

and mountain ranges.

-

Monitoring Earth's magnetic

field, apparently with their visual system and with tiny grains of

a mineral called magnetite in their heads

-

Observing the stars

-

Using the sun for guidance

-

Smell

-

And probably following their

neighbors (many birds migrate in large flocks)

Question: does it still

sound simple? I didn't think so. For example, birds which use

magnetic navigation must deal with a small problem -- magnetic north

is 1,600 kilometers from the north pole. That means migrants leaving

northern Alaska and following magnetic south would be travelling due

west!

Second, star navigation changes as

new constellations appear on the horizon as the birds travel north

or south.

Although birds have apparently been

overcoming these problems for millions of years, only in the past

year have scientists figured out how at least one species of bird

does it (see

Constant Compass Calibration). It seems that the birds

recalibrate their magnetic compasses against their star navigation

during their rest stops along the migration route. And if they don't

have enough time at the rests, they get lost.

Flight strategies

Once the birds know where they're going, they also need a way to get

there, and that brings us to the realm of fuel efficiency -- of

miles per rodent, or kilometers per thistle seed. Depending on their

size, route, and laziness (just kidding!), birds use one of these

flight strategies:

-

Slow and Steady Wins the Race:

The most basic technique is to keep flapping your wings until you

land. That's the technique used by the Canada goose and many other

migrants.

-

Soaring. Smarter (still kidding)

birds have figured out how to ride "thermals" -- updrafts of air

caused by solar heating, to take a free ride high into the sky.

These birds, including Swainson's hawk, turkey vultures, and many

others, only travel during the day, and only over land (preferably

flat land). Those restrictions can lead to astonishing

concentrations of

migrating

birds.

-

Flapping and gliding. These

birds flap their wings for a few beats, then glide for a while.

After they lose some altitude and/or speed, they flap some more.

-

Bounding. This is a combination

of flapping with a closed-wing glide. It's used by birds whose

wings would produce too much drag. Although their aerodynamic

bodies do create some lift, the birds tend to lose altitude and

the flight pattern is up-and-down, like the flap-and-glide

pattern.

Rapid Transit: the ins and

outs of bird migration

Let's face it--when it comes to dealing with winter, most birds seem

an awful lot smarter than humans. Instead of griping about the

weather, they simply head for a warmer climate. Let's look at a few

facts on bird migration:

-

What's the record for the longest

migration on the planet?

The arctic tern flies a phenomenal round trip that can be as long

as 20,000 miles per year, from the Arctic to the Antarctic and

back. Other sea birds also make astounding journeys: the

long-tailed jaeger flies 5,000 to 9,000 miles in each direction.

Arctic terns can migrate as far as 20,000 miles per

year.

-

The sandhill and whooping cranes

are both capable of migrating as far as 2.500 miles per year, and

the barn swallow more than 6,000 miles.

For the last word on bird migration, see the

Atlas of Bird Migration.

-

Why do about 520 of the 650 bird

species that nest in the United States migrate south to spend the

winter?

Because they get bored shivering in the dark. And because it's

bleak in the winter. And because there's nothing to eat. And

because their ancestors did it.

-

Why do some birds go north for

the summer?

Because there's more to eat. The 24-hour days near the Arctic

Circle produces a fantastic flowering of life. This brief, but

abundant, source of food attracts many birds (and mammals such as

the caribou) to the Arctic for breeding purposes.

-

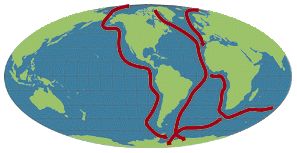

What influences migration

patterns over the long term?

Changes in climate (particularly ice ages), and shifts in the

positions of islands and continents as a result of tectonic drift.

-

How do they keep going?

Some birds store a special, high-energy fat before the trip.

Soaring raptors, for example, may not eat for several weeks as

they migrate. Other species eat along their migration routes.

-

How high can they fly?

Higher than Mt. Everest. Bar-headed geese have been recorded

flying across the Himalayas at 29,000 feet. Other species seen

above 20,000 feet include the whooper swan, the bar-tailed godwit,

and the mallard duck.

(Note: birds don't fly this high just to get in the Guinness book

of records, but rather to reach their destinations efficiently.

From radar studies, scientists know that birds can change

altitudes to find the best wind conditions. To fight a headwind,

most birds stay low, where ridges, trees and buildings slow the

wind. To ride a tailwind, they get up high where the wind is as

fast as possible.)

The world's largest

migration of raptors

(hawks, vultures, falcons, kites and other species) flies across

Mexico's Caribbean coastal plain near the city of Veracruz.

Raptor-watching is an old specialty

among birders--and thousands of eager birders flock to Cape May, New

Jersey to watch 50,000 of these elegant fliers make their way

between wintering and breeding grounds.

Photo

courtesy of the

Turkey Vulture Society. Photo

courtesy of the

Turkey Vulture Society.

But that is small potatoes compared

to the Veracruz migration, where 100,000 birds a day is not

unusual. Much of the credit for discovering this abundance of bird

life goes to Ernesto Ruelas, a Mexican biologist who has spent 10

years counting this

River of

Raptors.

Ruelas, who directs the Veracruz

office of Pronatura, an environmental organization, credits the

geography for funneling 3.3 million raptors through Veracruz each

year.

The funneling results from the

migratory habits

of the raptors. Most of the raptors are soaring birds, so

they depend on thermals to obtain altitude. Since the open sea does

not have thermals, they are restricted to the Mexican peninsula as

they fly between North America and points south. But they can't find

good thermals in the mountains which occupy much of Mexico west of

Veracruz--meaning they must stay near the coast.

As

a result, virtually the entire population of some raptors is flying

through a strip of land just 25 miles wide, and that means the

countryside is critical for survival of those species. "This is a

site that is capable of monitoring continental or worldwide

populations of certain raptors," says Keith Bildstein, research

director at

in Sanctuary

in Pennsylvania. As

a result, virtually the entire population of some raptors is flying

through a strip of land just 25 miles wide, and that means the

countryside is critical for survival of those species. "This is a

site that is capable of monitoring continental or worldwide

populations of certain raptors," says Keith Bildstein, research

director at

in Sanctuary

in Pennsylvania.

Like the monarch's wintering

grounds, the raptors' migration pathway points out how a

continent-wide population can depend on small tracts of land. Want

to read about the decline of

songbirds

which depend on isolated patches of summer habitat?

"Courtesy

University of Wisconsin Board of Regents." |