|

This is largely an account of my experience on

the spring, northward migration of the Gaddi shepherds of Himachal

Pradesh; from Kangra over into Bramour, Chamba district. But first I

should mention something of who the Caddis are and why they migrate.

Gaddi shepherds are not nomads. They

have homes, substantial village houses, and they own land which they

or their family cultivate, Their homeland is Gadderan, Bramour

tehsil, in the west of Chamba district. It comprises the valleys of

the upper Ravi and its tributary the Budil which form a V meeting at

Karamukhjust below Bramour. These two rivers here run more or less

east-west and divide the Dholar Dhar range to the south from the Pir

Pinjal to the north. Karamukh, the lowest point, is 4,500 ft., the

high peaks to the north over 19,000 ft. and the valley sides and

high alps are precipitous and inaccessible. The only road into

Gadderan is from Chamba, 50 km of a narrow, untarred, precipitous

'fairweather' road The country is surmounted by Mount Kailashl.

18,500 ft., the seat of Lord shiva and his consort Parvati. Gaddis

are staunch Shaivites and wherever they may wander, feel an

unusually strong cultural and religious involvement with their

homeland, also referred to as Shivbhumi, the land of Shiva. Gaddi shepherds are not nomads. They

have homes, substantial village houses, and they own land which they

or their family cultivate, Their homeland is Gadderan, Bramour

tehsil, in the west of Chamba district. It comprises the valleys of

the upper Ravi and its tributary the Budil which form a V meeting at

Karamukhjust below Bramour. These two rivers here run more or less

east-west and divide the Dholar Dhar range to the south from the Pir

Pinjal to the north. Karamukh, the lowest point, is 4,500 ft., the

high peaks to the north over 19,000 ft. and the valley sides and

high alps are precipitous and inaccessible. The only road into

Gadderan is from Chamba, 50 km of a narrow, untarred, precipitous

'fairweather' road The country is surmounted by Mount Kailashl.

18,500 ft., the seat of Lord shiva and his consort Parvati. Gaddis

are staunch Shaivites and wherever they may wander, feel an

unusually strong cultural and religious involvement with their

homeland, also referred to as Shivbhumi, the land of Shiva.

During the last hundred years or so many

Gaddis have bought land and built houses on

the southern slopes of the Dholar Dhar- the northern edge of Kangra

valley but whether or not they stiU have land or relations in

Bramour tehsil, they consider themselves as belonging to Gadderan.

It is thought that there are about 80,000 Gaddi

people. About half of these do not own flocks, and are

agriculturalists only. Of the 3,000 or so men who accompany the

flocks of sheep and goats, some take turns months at a time, in

shepherding and in cultivation with brothers, uncles or sons. Others

are away fron; home throughout the year except for a couple of weeks

in the spring and in the autumn when the flocks pass through their

own villages. It is nor the flocks that

dictate the annual pattern of the shepherds' 1ives.

The winter pastures are in an approximately

horizontal line in the foothills, south of the Dholar Dhar , from

Nurpur in the west to Bilaspul in the east. Here the flocks spend

four or five months, moving only locally from a base. The terrain is

scrub forest, semi-tropical jungle at 2 to 3,000 ft. Traditionally

it has .been the extent of available winter grazing that has

controlled numbers and the size of the flocks.

However recent cultivation and the increase in the domestic

head of cattle and goats are encroaching on these old pastures. The

shepherds at therefore anxious to move north as early as possible,

usually towards thc end of the month of chaet, about mid-April. But

how early depends entirely on how quickly the snow melts on the

higher passes and pastures. Last year, a year of particularly heavy

snow, they moved a month or so later than usual. migration from

Kangra over Jalsu, the lowest of the passes, and therefore the first

to be clear of snow The way was crowded with flocks and men, also

with women and children. For during the winter grazing months, as

opposed to the summer, some families do accompany the shepherds and

flocks Many others, in fact most of the Gaddi population of Bramour

, emulating the migratory movement of their flocks, come down in

winter to work with relations or live in rented accommodation in

Kangra. However recent cultivation and the increase in the domestic

head of cattle and goats are encroaching on these old pastures. The

shepherds at therefore anxious to move north as early as possible,

usually towards thc end of the month of chaet, about mid-April. But

how early depends entirely on how quickly the snow melts on the

higher passes and pastures. Last year, a year of particularly heavy

snow, they moved a month or so later than usual. migration from

Kangra over Jalsu, the lowest of the passes, and therefore the first

to be clear of snow The way was crowded with flocks and men, also

with women and children. For during the winter grazing months, as

opposed to the summer, some families do accompany the shepherds and

flocks Many others, in fact most of the Gaddi population of Bramour

, emulating the migratory movement of their flocks, come down in

winter to work with relations or live in rented accommodation in

Kangra.

(It is believed that even Lord Shiva moves from his

seat on Mount Kailash to winter at Pujalpur.) They were now on their

journey home, some taking a week, some two or more to reach their

villages. Everyone was full of chat. It was a real pleasure to be

one of the company. I had a glimpse of what it must have been like

on pilgrimages when large groups of people travelled on foot for

days at a time. Canterbury Tales-style jokes and incidents that you

have all shared are retold and embellished. Snippets of an old

woman's life and anecdotes about her relations soon make you feel

you know her well.

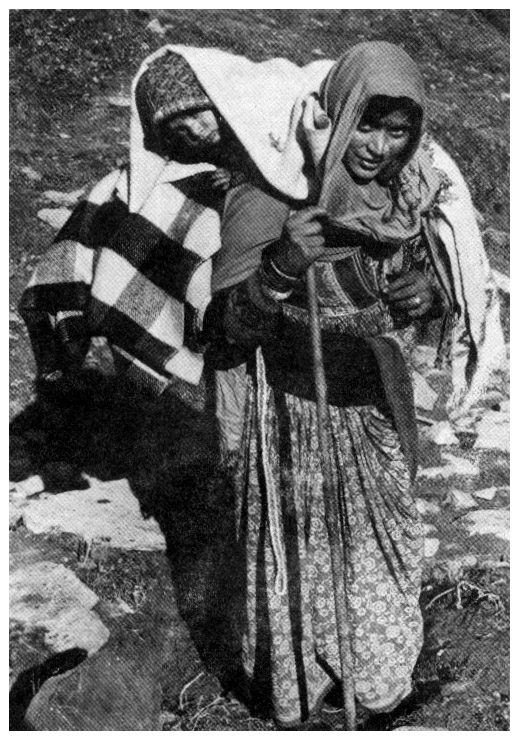

There were men and women who looked old

enough to have crossed this way twice a year for three score years

and ten, and there were babies of a few weeks. Then there were the

winter's purchases being taken home -chickens proudly carried in the

crook of an arm; handsome spotted house goats with large udders;

Jersey-type heifers and young bulls; baskets; winnowing trays;

Image By P R Bali plastic jerry cans; brightly-coloured nylon sweaters; radios;

dholkis, drums. Babies and young children are carried sideways,

across the rest of the luggage on the mother's or father's back.

They are often not tethered in a shawl, as is normal in the hills,

but perched, the parent casually holding on to a leg or foot while

the child's head dangles on the other side. Not everyone walks

exactly the same stage every day. Those with flocks and too many

young children or the old and infirm cover a shorter distance. Or,

like the old man and his daughter, the pleasure of whose company we

had the first morning, they may be detained by friends or relations

met along the way. when we were all dozing

after lunch our companion came to say how very much he had enjoyed

our company, as we had his but that the relations with flocks he had

met here would not let him go any further that day. He hoped we

would meet again. We did not think we would but several days later

at 5.30 am when we were packing up camp before climbing to the pass

he appeared on the skyline with his jolly, plump daughter puffing

and panting and holding up her skirts.

The day starts early.

Up before dawn and off soon after, walking with plenty of rests and

chats, until II or 12 o'clock when everyone stops to eat, and maybe

to cook, and then to smoke and snooze. Some walk another two or

three hours before settling for the night's camp. In places there

are what we in Scotland would call 'sheilings', though more often

the travellers shelter in caves -there were plenty on our route.

Everyone carries blankets.

Most of the hill women of

Himachal are free of the restrictions of purdah and excessive

modesty but the Gaddis or Gaddi women seem

to be particularly outgoing, friendly and full of self-confidence

-not just towards me, but to everyone, men too, The only exception

is that in the presence of any of their older male in-laws they

immediately cover their heads. They wear a distinctive and

attractive dress; the long, gathered skirts reminiscent of the

clothes depicted in old wood carving and miniature pictures of the

area. Over their head they wear a cloth, usually decorated with

floral embroidery which they work themselves. They have large

earrings, gold or silver, solid gold nose pieces, necklaces of

amber, silver, gold and pendants with fine enamelling- often

depicting Shiva and Parvati -or plain silver embossed pieces

commemorating their ancestors. Their chins are patterned with a

finely marked, circular tattoo, sometimes their hands and arms too.

Some wear a coat-dress of white homespun tweed down to the ground,

the lapels decorated with an embroidered flower. The more

fashionable version is a velvet blouse with broad cuffs, joined to a

very full skirt, reaching the ground, of colourful chintz. It takes

twelve yards of cloth and is forty four feet

at the hem which is lined with a contrasting colour and stitched

round and round many times. Whatever the style of the chaura, dress,

it is waisted with the dhora or woollen belt. The long chaura is

cumbersome to walk in, they often have to hitch it up. But a

Gaddini does not like to be seen out and about without it, though at

home she often strips down to the Punjabi- style salwar and kameez,

pyjamas and long overshirt, which she wears underneath. On the end

of her plait, on the blouse fastening, and often pinned on the

shoulder too, are the circular mirror medallions, decorated with

buttons and beads' that Gaddinis make and often give each other as

expressions of affection.

Every

woman I met asked me where my children were. Everywhere in India a

barren or unwed woman, is an object of pity, but the Gaddis go as

far as having to erect stones to quieten the spirits of childless

couples who disturb others' sleep. I was relieved to be able to say

my children were safely at home.

It is

hard to describe fully the all pervasive sheep and goatiness of that

journey. Whenever I glanced at a distant hillside, vaguely looking

at the skyline or the precipitous rocks, I would realise it was

'lifting' with the milk-white flocks. Clustered in an irregular

circle round a midday camp, moving imperceptibly across the hillside

grazing or following each other along an invisible path, like

maggots on the move. Nearby the endless baa-ing and bleating, the

calling, grunting and whistling - the whistling not as we would

imagine to their dogs but to the goats and sheep. One man always

leads, calling and whistling, another always at the back, grunting

and urging on the stragglers. As you walk

along the path the stink of wool and dung is overwhelming. Their

sharp little hooves eat away the path and the dung makes the rocks

slippery .If you are caught among a flock on a narrow path it is

maddening for they move at an irregular pace, their walk slower than

yours, but then they suddenly run on and those you had with ,

difficulty pushed your way past, have overtaken you. In camp the

baa-ing and bleating is all around, and the dung everywhere (and

immediately inside your tent). The vegetation is rank, nettles,

docks and thistles that grow where flocks habitually camp.

We

reached the top of the Jalsu Pass at about eight o'clock on a clear

morning. I had climbed the last steep stretch chatting to a new

behinji, sister, with a small baby, her husband and brother-in-law

and their flock. One-young male goat had to be pulled up and then

down the pass by the scruff of his neck. He had eaten kashmiri

patta, Rhododendron campanulata, which they do when hungry for

fodder and which makes them drunk. If several of the flock suffer at

once it causes the shepherd considerable inconvenience. We sat on

the snow at the top gazing at the sheer white beauty of Mount

Kailash. No one performed any prayers or sacrifices but all were

impressed by the view and by the first glimpse of the hills of home.

My new behinji 5 brothers insisted on my photographing them

with their largest male goat set against Mount Kailash. Then, 1,500

ft. down below, we settled on the gentian and primula-enamelled turf

and shared chappatti, of wheat or maize flour , and nettle and

bracken vegetable. We waited for a sad and lame old man, who had

recently sold his flock and who was finding it hard to negotiate the

steep snow. So was a very fat and prosperous woman, wife of a

Brahmin travelling with four or five young girls, cows, goats, and

newly purchased household goods. But everyone had the breath of home

in their nostrils and were soon off trippeting down through the

rhododendrons -they had now taken off their goat-hair snow socks.

That

night was particularly noisy. My new sister walked up and down the

path her baby screaming; after that day's exertions she had no milk

for it, neither did their goats. We gave her some dried milk but it

obviously was not appreciated as the baby cried all night and so did

all the kids and lambs.

The Gaddis are staunch devotees of Lord

Shiva and Parvati, in her many guises, as the following incident

illustrates. Before reaching the Ravi river, I and many others, men,

women and children, were coming down a 1,000 ft. drop to cross a

tributary .On the opposite side the path was equally steep. Halfway

up it a shepherd began to take his flock off the track. They

scattered across the precipitous hillside to graze. One of our Gaddi

companions bellowed across the gorge ordering the shepherd not to do

so as stones would fall-on the people climbing up. The shepherd paid

no heed; We all settled on a rock on the nearside to wait until the

flock moved on and the danger of falling stones was over. As we

watched, a fully grown sheep came hurtling down through the air,

legs stretched out, and fell with a deathly thud on the path. It was

an aweful sight: everyone gasped. And then, in the river bed, when

we did cross by a rickety bridge, the new PWD one having been washed

away, there was a newly dead cow with a broken neck. On the far side

at the top we found there was a temple to Lakhna devi, a form of

Parvati, the presiding deity of the area whose power had just been

so dramatically illustrated. One of the shepherds of the ill-

mannered and ill-fated flock was sitting by the temple. He was

roundly abused. 'What do you think you were doing, taking flocks

across a hill like that in the middle of the day with mothers and

children walking up the path below? What sort of Gaddi do you think

you are? See, you have no respect for the devi. And it was also

explained hat the owner of the cow, nearing the end of his five day

journey from Kangra, was drunk, had lost his temper and hit his cow

on the steep slope which made her lose her balance and fall to her

death. All agreed that in the face of such wanton lack of respect,

the deity was justified in asserting her power . The Gaddis are staunch devotees of Lord

Shiva and Parvati, in her many guises, as the following incident

illustrates. Before reaching the Ravi river, I and many others, men,

women and children, were coming down a 1,000 ft. drop to cross a

tributary .On the opposite side the path was equally steep. Halfway

up it a shepherd began to take his flock off the track. They

scattered across the precipitous hillside to graze. One of our Gaddi

companions bellowed across the gorge ordering the shepherd not to do

so as stones would fall-on the people climbing up. The shepherd paid

no heed; We all settled on a rock on the nearside to wait until the

flock moved on and the danger of falling stones was over. As we

watched, a fully grown sheep came hurtling down through the air,

legs stretched out, and fell with a deathly thud on the path. It was

an aweful sight: everyone gasped. And then, in the river bed, when

we did cross by a rickety bridge, the new PWD one having been washed

away, there was a newly dead cow with a broken neck. On the far side

at the top we found there was a temple to Lakhna devi, a form of

Parvati, the presiding deity of the area whose power had just been

so dramatically illustrated. One of the shepherds of the ill-

mannered and ill-fated flock was sitting by the temple. He was

roundly abused. 'What do you think you were doing, taking flocks

across a hill like that in the middle of the day with mothers and

children walking up the path below? What sort of Gaddi do you think

you are? See, you have no respect for the devi. And it was also

explained hat the owner of the cow, nearing the end of his five day

journey from Kangra, was drunk, had lost his temper and hit his cow

on the steep slope which made her lose her balance and fall to her

death. All agreed that in the face of such wanton lack of respect,

the deity was justified in asserting her power .

As we

reached cultivation, gradually our companions began to peel off. The

fraternity of the pilgrimage spirit began to loosen as the

excitement of nearing home increased, 'Kangra is better than here in

the winter, but there you never feel hungry. It's the water (we

would say "it's the air"). Here you enjoyed your

food.

Here the

mountains go straight down into the river gorges. From the bottom of

the valley you can see nothing, only hear the infernal noise of the

river; in fact it is difficult to imagine that there are villages

above. But up at the level of the major villages, 1,000 ft. or so

above, there are views on a scale that defy ordinary visual

conception and mock the camera's lens. Shiny snow peaks are clearly

chiselled in the morning or evening sun; one-dimensional and

ethereal in the moonlight.

Waterfalls cascade in white sprays down the rock faces. There

are dark forests of deodar, spruce and fir, particularly on the

north-facing slopes. On the south-facing slopes, the alps, sometimes

even very high up, are stripes of deep green or yellow: These are

tiny cultivated terraces, some so narrow that the terracing has to

be open-ended to allow the bullocks and plough to turn. Some must be

dug by hand for the bullocks could not even walk on the precipitous

slope.

The

villages which had been shut up for the winter had a slightly

haunted feeling. Will the owners reappear? The heavy wooden doors

are padlocked, the locks dusty from disuse. The house shrines in the

courtyards obviously unattended. As all the cattle are left in the

charge of the few families who remain, the byre doors which are on

the ground floor are plastered over with mud and dung; sometimes

crumbled at the corners by hungry rats trying to get in. The only

signs of life were the bees flying into their hives - hollowed

sections of timber set into the walls.

The

owners do not arrive all at once, but spread over a month or so.

There was no flurry of excitement, nor outward signs of emotion. The

greeting of a younger to an elder, as in India everywhere, is to

touch the elder's feet. Hence between family members they touch the

feet and then embrace, on each side twice. I saw a young shepherd

returning with his flock climbing the hill. Seeing his sister-in-Iaw

on the stone balustrade of the house he took a red hankerchief out

of his pocket to cover his head before greeting her. Schoolboys,

twelve or thirteen year olds, were climbing the 1,000 ft. from

school, poking, their hands down into the stone seat by the temple

where they had left their, very unripe, apricots when on the way to

school in the morning. At that moment an elder brother or cousin

came along the hill with his returning flock. There was no greeting,

no sign of joy on either side, but 'Hey, Chandu, take my luggage

home', and he dropped his blanket-wrapped pack on the path for the

young fellow to pick up.Heaps of manure, accumulated the previous

year and matured during the winter lay in the yards or on the path,

ready to be carried out to fertilize the maize fields. Bedding

quilts, made of old bits of tweed blankets roughly quilted, were

spread out in the sun to air. Fields must be ploughed, grain that

has been stored all winter cleaned and dried, and flocks must be

clipped before they move on away for the summer. But there was

no bustle or hustle; plenty of time to sit on the verandah or on the

stone balustrade and gently smoke a hookah and chat.

Witnessing this calmly congenial scene it was hard to imagine

that for the shepherds it was but a brief interlude. That within

days they would move on north and up to the summer grazings -handed

on from generation to generation, taxed by the forest department and

sometimes by the villagers too. Some move to high pastures not so

very far from home, but still with dangers of avalanches, crevasses,

falling stones, and bears. It is a life of discomfort, with the

constant necessity of keeping an eye on each sheep and goat. Others

must walk Over the 16 to 17,000 ft. passes, and perhaps hundred

miles to graze their flocks on the 'blue' and nutricious grass of

Lahoul and Spiti, even to the borders of Ladakh and Tibet. There to

spend two or three months in a treeless land, their food, goat's

milk and parched barley flour that requires no cooking, or sometimes

dhal and rice or makke ka Toti, maize chappattis cooked on acrid

smelling yak or cattle dung. They have no shelter but their blankets

and kilted white homespun cloaks, sometimes a dry stone igloo. The

only sounds that relieve the monotonous baa-ing of their flocks, the

cold wind and their own flutes.

As I sat

envisaging their summer, something that had been gradually occurring

to me became quite clear . Gaddis may consider shepherding their

dharma given to them by Lord Shiva. But it is not just that that

makes them follow their ancestors' migratory life. Nor , is it a

love of it (to me a romantic life). It is the prosperity that the

sheep and goats bring -the former largely from wool, the latter from

meat. If the Gaddis lived solely from the cultivation of those tiny

strips of terracing there would not be so many newly built houses on

the opposite hill, shops filled with shoes, cloth, dalda and

suchlike, nor women laden with jewellery, nor substantial

land owned by them in Kangra. And were it not for their comparative

prosperity and their travelling habits, combined with a pride in

their homeland and culture, would they have the outgoing and

friendly manner which had made this journey such a pleasure for me.

|