|

Early Life

Alexander the Great was the son of King Philip II of Macedon and of

his fourth wife, Epirote princess Olympias. According to Plutarch

(Alexander 3.1,3), Olympias was impregnated not by Philip, who was

afraid of her, and her affinity for sleeping in the company of

snakes, but by Zeus Ammon. Plutarch (Alexander 2.2-3) relates that

both Philip and Olympias dreamt of their son's future birth.

Olympias dreamed of a loud burst of thunder and of lightning

striking her womb. In Philip's dream, he sealed her womb with the

seal of the lion. Alarmed by this, he consulted the seer Aristander

of Telmessus, who determined that his wife was pregnant and that the

child would have the character of a lion.

Aristotle was Alexander's tutor; he gave Alexander a thorough

training in rhetoric and literature and stimulated his interest in

science, medicine, and philosophy. After his visit to the Oracle of

Ammon at Siwa, according to five historians of antiquity (Arrian,

Curtius, Diodorus, Justin, and Plutarch), rumors spread that the

Oracle had revealed Alexander's father to be Zeus, rather than

Philip. According to Plutarch (Alexander 2.1), his father descended

from Heracles through Caranus and his mother descended from Aeacus

through Neoptolemus and Achilles. Aristotle gave him a copy of the

Iliad and a knife that he always hid under his pillow at night.

Invasion of India

Coin commemorating Alexander's campaigns in India, struck in Babylon

around 323 BC.

Obv: Alexander standing, being crowned by Nike, fully armed and

holding Zeus' thunderbolt.

Rev: Greek rider, possibly Alexander, attacking an Indian

battle-elephant, possibly during the battle against Porus.With the

death of Spitamenes and his marriage to Roxana (Roshanak in

Bactrian) to cement his relations with his new Central Asian

satrapies, in 326 BC Alexander was finally free to turn his

attention to India. Alexander invited all the chieftains of the

former satrapy of Gandhara to come to him and submit to his

authority. Ambhi, ruler of Taxila, whose kingdom extended from the

Indus to the Hydaspes (Jhelum), complied. But the chieftains of some

hilly clans including the Aspasios and Assakenois sections of the

Kambojas (classical names), known in Indian texts as Ashvayanas and

Ashvakayanas (names referring to their equestrian nature) refused to

submit.

Alexander personally took command of the shield-bearing guards,

foot-companions, archers, Agrianians and horse-javelin-men and led

them against the Kamboja clans -- the Aspasios of Kunar/Alishang

valleys, the Guraeans of the Guraeus (Panjkora) valley, and the

Assakenois of the Swat and Buner valleys. "They were brave people

and it was hard work for Alexander to take their strongholds, of

which Massaga and Aornus need special mention" (Alexander the Great,

2003, p 123, I. Worthington). A fierce contest ensued with the

Aspasios in which Alexander himself was wounded in the shoulder by a

dart but eventually the Aspasios lost the fight; 40,000 of them were

enslaved. The Assakenois faced Alexander with an army of 30,000

cavalry, 38,000 infantry and 30 elephants (Curtius). They had fought

bravely and offered stubborn resistence to the invader in many of

their strongholds like cities of Ora, Bazira and Massaga. The fort

of Massaga could only be reduced after several days of bloody

fighting in which Alexander himself was wounded seriously in the

ankle. When the Chieftain of Massaga fell in the battle, the supreme

command of the army went to his old mother Cleophis (q.v.) who also

stood determined to defend her motherland to the last extremity. The

example of Cleophis assuming the supreme command of the military

also brought the entire women of the locality into the fighting

(Ancient India, 1971, p 99, Dr R. C. Majumdar; History and Culture

of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, Foreign Invasion, p 46,

Dr R. K Mukerjee). Alexander could only reduce Massaga by resorting

to political strategem and actions of betrayal. According to Curtius:

"Not only did Alexander slaughter the entire population of Massaga,

but also did he reduce its buildings to rubbles". This statement

clearly shows that Alexander had suffered severe losses at the hands

of the Assakenois so that he must have lost his poise and given vent

to his wrath on the buildings of Massaga.

The Assakenois were a brave people and fierce fighters but lost the

battle because of their over-confidence and lack of cunning &

political-sagacity (S Kirpal Singh).

A similar man-slaughter then followed at Ora, another stronghold of

the Assakenois.

In the aftermath of general slaughter and arson committed by

Alexander at Massaga and Ora, numerous Assakenian people fled to a

high fortress called Aornos. Alexander followed them close behind

their heels and captured the strategic hill-fort but only after

fourth day of bloody fight. The story of Massaga was repeated at

Aornos and a similar carnage on the tribal-people followed here too.

Writing on Alexander's campaign against the Assakenois, Victor

Hanson comments: "After promising the surrounded Assacenis their

lives upon capitulation, he executed all their soldiers who had

surrendered. Their strongholds at Ora and Aornus were also similarly

stormed. Garrisons were probably all slaughtered” (See: Carnage and

Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power, 2002, p 86,

Victor Hanson).

Sisikottos who had helped Alexander in this compaign was made the

governor of Aornos.

After reducing Aornos, Alexander crossed the Indus and fought and

won an epic battle against Porus, a ruler of a region in the Punjab

in the Battle of Hydaspes in (326 BC). After the victory, Alexander

was greatly impressed by Porus for his bravery in battle, therefore

he made an alliance with Porus and appointed him as satrap of his

own kingdom and even added some land he did not own before.

Alexander then named one of the two new cities that he founded,

Bucephala, in honor of his noble mount who had brought him to India.

Alexander continued on to conquer all the headwaters of the Indus

River.

East of Porus' kingdom, near the Ganges River, was the powerful

empire of Magadha ruled by the Nanda dynasty. Fearing the prospects

of facing another powerful Indian army and exhausted by years of

campaigning, his army mutinied at the Hyphasis (modern Beas),

refusing to march further east. Alexander, after the meeting with

his officer, Coenus, was convinced that it was better to return.

Alexander was forced to turn south, conquering his way down the

Indus to the Indian Ocean. He sent much of his army to Carmania

(modern southern Iran) with his general Craterus, and commissioned a

fleet to explore the Persian Gulf shore under his admiral Nearchus,

while he led the rest of his forces back to Persia by the southern

route through the Gedrosia (present day Makran in southern

Pakistan).

After India

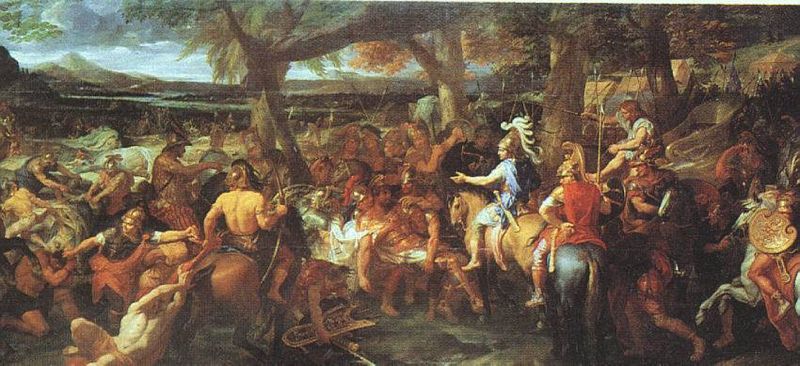

Alexander and Porus by Charles Le Brun, 1673.Discovering that many

of his satraps and military governors had misbehaved in his absence,

Alexander executed a number of them as examples on his way to Susa.

As a gesture of thanks, he paid off the debts of his soldiers, and

announced that he would send those over-aged and disabled veterans

back to Macedonia under Craterus, but his troops misunderstood his

intention and mutinied at the town of Opis, refusing to be sent away

and bitterly criticizing his adoption of Persian customs and dress

and the introduction of Persian officers and soldiers into

Macedonian units. Alexander executed the ringleaders of the mutiny,

but forgave the rank and file. In an attempt to craft a lasting

harmony between his Macedonian and Persian subjects, he held a mass

marriage of his senior officers to Persian and other noblewomen at

Susa, but few of those marriages seem to have lasted much beyond a

year.

His attempts to merge Persian culture with his Greek soldiers also

included training a regiment of Persian boys in the ways of

Macedonians. It is not certain that Alexander adopted the Persian

royal title of shahanshah ("great king" or "king of kings").

However, most historians believe that he did.

Alexander let it be known that he intended to launch a campaign

against the tribes of Arabia. After they were subjugated, it was

assumed that Alexander would turn westwards and attack Carthage and

Italy.

After traveling to Ecbatana to retrieve the bulk of the Persian

treasure, his closest friend (and possible lover) Hephaestion died

of an illness. Alexander was distraught and on his return to

Babylon, he fell ill and died.

|